by Ty Slobe

Last July when I got to Chile, the girls in my exchange program started complaining right away about street harassment. Our program director told us that we should get used to it, that it is “part of the culture,” that we should be flattered. At that point I had already taken enough strolls around the sexual harassment block to know that it was not something that any of us were going to get used to, that it is not something that anyone should get used to, but the last two aspects of what she said struck me as particularly strange.

Last July when I got to Chile, the girls in my exchange program started complaining right away about street harassment. Our program director told us that we should get used to it, that it is “part of the culture,” that we should be flattered. At that point I had already taken enough strolls around the sexual harassment block to know that it was not something that any of us were going to get used to, that it is not something that anyone should get used to, but the last two aspects of what she said struck me as particularly strange.

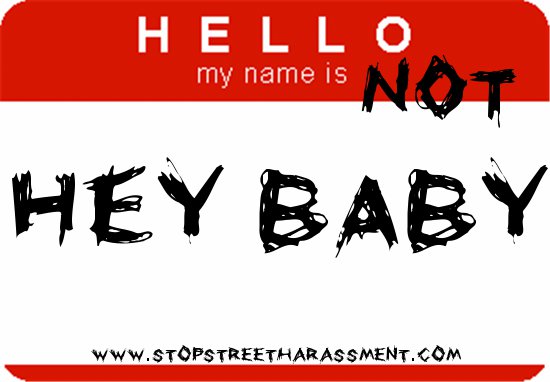

I’m not buying that street harassment is something that is a result of any particular country’s culture, nor that there are stereotypical womanizers who can be identified by their society of origin. Obviously I am also not buying the idea that I should be flattered by being whistled at by some creeper yelling at me across four lanes of speeding traffic. As a tribute to the man last Thursday who ran his hands through my hair when I was walking through a group of people and the guy this weekend who touched my face and made me cry, I think that this is a topic worth talking about. I want to let everyone know that I am not an object to be touched and whistled at in the street. I’m not an object at all. Women are people, not objects.

That is exactly what street harassment is: making women feel like objects, making women feel like the reason they are outside is so that men can enjoy looking at their bodies, making women afraid to go outside. It is really a terrifying thing, feeling like you are a tiny little thing next to a big group of men who could attack you, and who do very frequently take harassment beyond sly whispers and low-pitched whistles. It is terrible to constantly be reminded that there are so many people physically bigger than you who could harm you and who feel the need to remind you of their power through harassment every time you go outside. It makes you feel helpless, it is belittling, it is objectifying.

I know that I am not the only person who could write a novel on personal street harassment stories—everyone woman I know has had the same experiences. According to a study from Cornell University and Hollaback!, “any type of harassment (i.e., verbal, groping, assault) could produce extreme feelings of fear, anger, shame, etc. This indicates that it may be the violation of being harassed, rather than the specific behavior, that is one of the main drivers of a target’s emotional response.” Meaning, I am also not alone in feeling disgusted and degraded by street harassment in all of its colorful forms. For more information on how to stop the objectification and discomfort that we feel in the street visit Hollaback!’s website and see all of the amazing things that they are doing to fight back in Santiago and all around the world.

The thing, though, is that it is only one form of objectification of the female body, which is why I am not convinced that it is just something that is “part of the Chilean culture.” Objectifying women could not possibly be specific to one culture, because it is something that we see everywhere in the media as well. Maybe street harassment is a more personally intense and (literally) in-your-face experience, but it is certainly not the only place where societies are teaching us that women are objects to be bought, sold, poked, harassed, abused, and belittled.

It’s really no wonder that I feel like a tiny nothing in the street whenever someone whistles at me, considering the contrast of the “defenseless” female body juxtaposed to the “powerful” male body in so many advertisements. It is also, unfortunately, not very hard to believe that so many men treat women as though our presence in the street is for their own pleasure, considering the fact that the female body is so often turned into a product for male pleasure by the media. Street harassment goes far beyond the streets of a few cities, or the “norms” of a few cultures. It has to do with objectification of the female body, and it is a global epidemic.

One could argue that having a stranger whisper “sexy mama” in your ear as you are waiting for the bus is flattering. One could also argue that the exploitation of the beautiful female body in advertising is flattering. Our bodies are not bottles of alcohol, we are not toys, we are not sex-things, we are not food, and violence against us should never be used for advertising purposes. Media that objectifies women has real consequences, and being objectified in the streets is only the visible surface of them.

I do not know which is scarier, having a stranger touch my hair in the street or the normalization of objectification of the female body for advertising purposes. Either way, I’m not an object. No matter who you are or where you come from, stop trying to make me one. I am a person.

[…] Partnerships galore. This week we spoke with Wagner College and Sisters on the Runway, an organization that has raised over $50,000 toward ending domestic violence. We also got a shout-out from our partners at SPARK, check it out. […]

I 100% support your view and also am disgusted at the ‘acceptable’ and ‘flattering’ labels attatched to street harrassment. I am a young woman comfortable with myself and like to look good FOR MYSELF. I find it insulting and degrading when men (and female abuser apologists) assume that the way I dress is to incite a sexual response from men. As a married woman in a secure relationship, my desires when I dress do not contemplate the penises or sexual aggression I may encounter- I just want to feel happy with myself. I will not change my style of clothes but i will speak about the harrassment without guilt and shame. I will ask women to support eachother and not accept degradation. I will teach my son to love and respect women and i will ask other mothers to do the same. I am a 3Dimensional soul and I refuse to be graded as a 1Dimentional image. WOMEN ARE NOT OBJECTS!

The only problem that I have with what you said is that men assume that you dress the way that you do to incite a sexual response, when the truth is that you incite an (involuntary) sexual response no matter how you dress. Most men have sufficient impulse control to mask what they are feeling.