This post is part of the 2013 Feminist Reads Challenge. To learn more about the challenge or join in, click here.

by Katy Ma

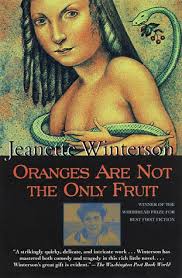

In June I was excited to discover that our summer reading books for AP Literature were feminist-friendly—Jane Eyre and Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit–both of which exceeded my expectations on so many levels. I would love to discuss my appreciation for Jane Eyre another time, but today I’d like to share more about the winner of the Whitbread Prize for Best First Fiction—Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson, the fictional story of a quirky girl adopted into a radically religious household who comes to terms with her sexuality and learns to define religion for herself.

Not the Only Fruit–both of which exceeded my expectations on so many levels. I would love to discuss my appreciation for Jane Eyre another time, but today I’d like to share more about the winner of the Whitbread Prize for Best First Fiction—Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson, the fictional story of a quirky girl adopted into a radically religious household who comes to terms with her sexuality and learns to define religion for herself.

After first reading a brief synopsis about the book, I was slightly anxious with fear that I wouldn’t be able to fully relate to Jeanette (the main character, who coincidentally—or not—shares the same name as the author) because of the disparities in our childhoods. My family is Christian, but I never felt my religion to be burdensome or restricting, or found that the congregations we have been apart of to be “radical,” like Jeanette’s. I also feared that I would have trouble identifying with Jeanette’s struggle with her sexuality, since I am straight. I harbored so many preconceived notions about how it would be religion slamming and filled with confusing metaphors I wouldn’t understand (what’s “oranges” got anything to do with anything?!

Then I read the book.

I won’t lie: it was frustrating at first. Lots of seemingly obscure references and scenes that make sense only the second time you read the book or revisit them after you’ve finished (I had many “ohhh so that’s what that means…” moments). I was puzzled by the beginning of the book especially since I had a vague idea of where it was supposed to end, but the pieces were scattered and I didn’t know how it was going to take me from point A to point B. But I trusted it to make sense, and eventually, it did. This book takes some patience to attack, but I found that having faith in the destination was what allowed me to appreciate the journey of getting there.

Jeanette is an incredibly innocent girl with the best intentions, who has the unfortunate task of existing in a bubble where she goes completely unappreciated and misunderstood by the vast majority of people in her life including her parents, teachers, peers, and congregation members. She has an affinity for preaching and is totally devoted to her relationship with God. But when it’s “revealed” that she prefers relationships with other women, the stability of her household and congregation crumbles, and Jeanette is left to pick up the pieces while still trying to figure out why her sexuality renders her to be so hatefully rebuked by those closest to her (hint: they try performing an exorcism on her, to extract the “demons”). Without revealing the ending, I’ll just say that Jeanette inevitably learns that she must define religion for herself.

Now let me backtrack. I got the hint that Jeanette the character was more or less allegorical to Jeanette the author, but I curious how much of a correlation existed. I wondered if the story was possibly an altered account of Winterson’s own personal experiences growing up. I looked up her biography, and realized that the autobiographical aspect was far larger than I had suspected.

Winterson was adopted by working-class Pentecostal parents who raised her in Accrington, England where she had access to only 6 books–the Bible and other religious texts, of course, being among them. Her parents largely disapproved of her reading literature, unless it was the Bible. They wanted her to become a missionary, a path far different from the one Winterson would actually take. At the age of 16, she left her conservative home after falling in love with another girl. She supported herself with odd jobs (one being working at a lunatic asylum) while she took college entrance exams. She was in and out of schooling, but eventually found herself studying English at Oxford University. There, at only the age of 23, she wrote Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit.

Winterson was adopted by working-class Pentecostal parents who raised her in Accrington, England where she had access to only 6 books–the Bible and other religious texts, of course, being among them. Her parents largely disapproved of her reading literature, unless it was the Bible. They wanted her to become a missionary, a path far different from the one Winterson would actually take. At the age of 16, she left her conservative home after falling in love with another girl. She supported herself with odd jobs (one being working at a lunatic asylum) while she took college entrance exams. She was in and out of schooling, but eventually found herself studying English at Oxford University. There, at only the age of 23, she wrote Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit.

I was stunned to realize that Oranges was more or less a reflection of her childhood and young adult life. Many of the events in Winterson’s life are noted through the lens of Jeanette, in slightly altered forms. Realizing this element prompted me to appreciate her work even more.

Here are some of my favorite quotes from the novel of Jeanette acknowledging the complexity of her struggles:

Everyone who tells a story tells it differently, just to remind us that everybody sees it differently. Some people say there are true things to be found, some people say all kinds of things can be proved. I don’t believe them. The only thing for certain is how complicated it all is, like string full of knots. It’s all there but hard to find the beginning and impossible to fathom the end. The best you can do is admire the cat’s cradle, and maybe knot it up a bit more.

“Everyone thinks their own situation most tragic. I am no exception.”

“I miss God. I miss the company of someone utterly loyal. I still don’t think of God as my betrayer. The servants of God, yes, but servants by their very nature betray. I miss God who was my friend. I don’t even know if God exists, but I do know if God is your emotional role model, very few human relationships will match up to it.”

“I seem to have run in a great circle, and met myself again on the starting line.”

This is a novel I’m sure I’ll return to in the future. I thoroughly enjoyed the vivid first-person experience through Jeanette’s character, and would highly recommend it to anyone looking for a novel that combines controversial elements of religion, sexuality, and feminism without being burdensome or didactic. After reading “Oranges,” I gained a better understanding of what it means to define religion for myself. Jeanette taught me that human relationships and communities will always be complex, and that’s just the way it is. What’s more important is to focus on finding your own truths and surrounding yourself with people who genuinely love you for the content of your character.