This post is part of #ReadWomen2014.

by Alisha Pavelites

People often gauge the validity of a female character’s experience in a story by how “strong” she is. We hear “more strong female leads!” all the time. To be honest, saying “we need strong female leads” takes away from the real issue: we just need more women. Women and girls don’t just need “empowered” women in their stories, we need realistic women. Women we can relate to. The issue with reading literature about women written by men is that it exists in the male fantasy of what they believe women to be. A lot of our heroines come from the male imagination, often as sidekicks or romantic interests.

all the time. To be honest, saying “we need strong female leads” takes away from the real issue: we just need more women. Women and girls don’t just need “empowered” women in their stories, we need realistic women. Women we can relate to. The issue with reading literature about women written by men is that it exists in the male fantasy of what they believe women to be. A lot of our heroines come from the male imagination, often as sidekicks or romantic interests.

Think of Sherlock Holmes. Not just brilliant, but moody, addicted to drugs, sometimes funny (always witty), sometimes angry, a lot of the times cool and collected. Now turn him into a watery half-human half-invertebrate who is incomplete without romance. Erase all his dimensions and complexity. You’re left with a flat, uninteresting character who’s annoying to read, because Sherlock Holmes without all the dimensions of Sherlock is just a guy who likes to solve mysteries.

It’s not like women haven’t taken up their pen and paper since the dawn of literature and started writing realistic women. But instead, we hear about John Green and how “realistically” he portrays the teenage girl experience with “brutal honesty.” The Fault in Our Stars is Green’s debut novel centered on Hazel Grace Lancaster, a female protagonist who reads as a secondary character in her own story about living with cancer and falling in love. She’s the “main character,” but she doesn’t really exist without cancer or her love interest.

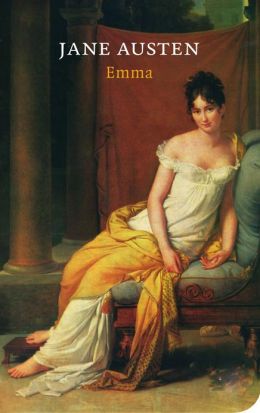

Jane Austen’s Emma is a fine starting point, or middle point, for venturing into the world of the female lead written by a woman. Emma Woodhouse is the protagonist of her story, and the narration follows her life in detail as she tries to play matchmaker for her friends and family. What makes Emma so interesting is that Jane Austen didn’t really write her to be likeable or relatable to anyone. Emma is rich, “handsome,” and pretty smart (according to Emma). She’s a snob, and though she does good deeds, she often does them out of believing she’s on a moral high ground or doing good for the poor souls beneath her status. The book reveals Emma’s faults in an ambiguous way. Austen never emphasizes whether Emma is “good” or “bad.” She’s a person; she’s a human being who doesn’t exist to prove some point about how women are strong and capable—but still can be interpreted as a very capable and intelligent woman.

Emma leaves such an impression on me because among classics written by men, there’s so much categorizing women into either “that bitch that won’t date me” or “that slut who dates everyone” or “my mom” (albeit in more formal and flowery terms–see The Great Gatsby); it’s refreshing to read a girl from a girl’s point of view. It wears on a young woman’s soul to read shallow female characters in literature written by men who if they don’t have some sappy love interest for their hulking hero—girl’s just cease to exist for Some Mysterious Reason.

In Emma, seventeen year old Harriet Smith lives in a local boarding school and is introduced in the story as “the natural daughter of somebody.” Emma takes it upon herself to treat her as an improvement project (out of love and selflessness, of course), and thus intervenes when a farmer proposes to Harriet. Emma had plans for Harriet to be married to someone of a higher social status. Since nobody knows Harriet’s parents, Emma is free to make up stories about Harriet’s noble place in society.

Emma writes the rejection letter to the farmer who proposes to Harriet, and is later very humbled when she finds out that Mr. Elton, the man who she wanted Harriet to marry, has intentions of marrying Emma. Therefore, she had ruined a pretty good match between Harriet and the farmer because of her own sense of superiority. She realizes this later, and apologizes to Harriet.

Jane Austen is clever, funny, and honest. It shines through in Emma Woodhouse, one of the finest literary heroines. And yeah, you may have to have a dictionary beside you to get through Emma. It’s totally worth it though, it’s cute in a refined way and has some lovely, non-sappy romance dabbled throughout. Emma embarrasses herself, she falls in love, she makes me mistakes and she is unapologetically human.

You can read it here.